No one likes playing second fiddle. Especially, when that fiddle has been played year after year. However, for the first time in recent memory, Sotheby’s has overtaken its rival Christie’s in terms of sales. The auction duopoly is used to battling it out and vying for the top spot, but this time it feels different. Sotheby’s has adopted a mindset that is more commonly associated with tech companies than 300-year-old institutions. So let’s dissect Sotheby’s new growth strategy and explore why I think this is not just a one-off fluke.

Why cash was king

Before we kick off, I want to clarify that Sotheby’s and Christie’s are not giants resting on their past achievements. The two companies are fiercely competitive and constantly innovating. However, this innovation has largely been confined to the art space. Sotheby’s tried its hand in real estate but decided to stick to licensing its brand name out rather than playing an active part in it.

As we discussed previously, the art world is very different to many other industries. The uniqueness of each work of art makes scaling operations difficult. That’s just one reason why the art industry itself is unique to other creative industries. Innovation happened in how the auction houses convinced art sellers to instruct them. In the late 1980s, Sotheby’s for example innovated on the financial incentives it gave sellers.

These new financial incentives meant that whichever company had the deepest pockets at that time was likely to win the seller’s consignment. Both Christie’s and Sotheby’s have been providing seller incentives to this day.

Like many other marketplaces, the seller creates the supply and so auction houses chase after those collectors with high-value art pieces. They are not just high value in terms of price, but also in terms of potential PR value and in terms of attracting interested buyers. This is why the art market thus far has been supply-side driven.

To buyers, auction houses are commodity suppliers with little differentiation between them other than what they are auctioning off. Even the commission a buyer pays (known as the buyer premium) is pretty much identical across both top auction houses. This dynamic has led to both Christie’s and Sotheby’s offering ever-greater concessions, guarantees and lower fees to sellers just to secure high-profile artwork for their auctions.

Though the battle for ever bigger seller guarantees was initiated by Sotheby’s, Christie’s eventually took over. By becoming a privately held company owned by French billionaire Francois Pinault, it just had a bigger chequebook and didn’t have to justify everything it did to the public markets. Christie’s had the benefit of a long term view and financial muscle which led to it overtaking the publicly traded Sotheby’s in terms of sales.

However, in 2019 Sotheby’s was bought out and taken private, essentially negating Christie’s earlier advantage. But this was only an opening play. In order to understand how Sotheby’s came out ahead, we need to look at the decision-making factors that drive art sellers to choose an auction house for the sale of their art.

The psychology of an art seller. And how Sotheby’s created a competitive edge

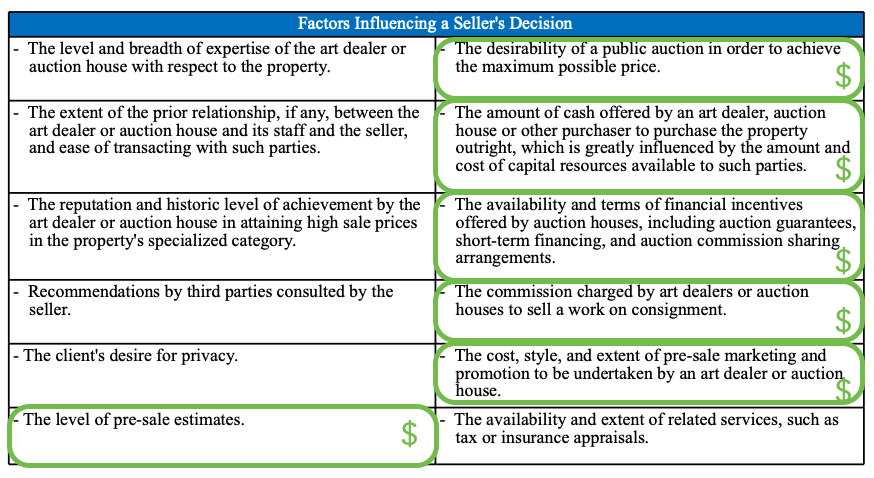

Sotheby’s published a very helpful table (see below) in its 2018 annual report highlighting the main factors that sellers take into account when deciding who to sell with. Note that 50% of the twelve points are direct financial factors. Financial matters rule when a seller decides whether Christie’s, Sotheby’s or any other auction house will get the sale.

Source: Sotheby’s 2018 annual report

This is the reason why Sotheby’s initiated seller guarantees, minimum and reserve prices in the first place. But it meant that Sotheby’s had commoditised itself to the extent that Christie’s could copy its strategy and beat it by offering better incentives.

One area that Sotheby’s has an edge over Christie’s is in being able to offer specialist short-term and long-term art financing via its finance arm. This serves as an interesting customer acquisition strategy whereby the company strengthens its relationship with potential sellers. Even better is that it can do so at a profit.

Sotheby’s average loan is near the $500,000 mark and it only lends around about 50% of the underlying artwork’s value and charges a decent interest rate for the pleasure. If the borrower defaults, Sotheby’s gets the artwork since it’s the collateral. Its art expertise and access to private transactions data give it an edge over traditional lenders and even specialist art financing houses. And since Christie’s does not offer anything similar, it means Sotheby’s can deepen its relationships with certain art collectors.

But not all wealthy art collectors are in need of a loan. And Sotheby’s doesn’t want a race to the bottom with its competitors on offering financial incentives for the other sellers it has not yet engaged with. Therefore, the company decided it had to expand its pool of possible buyers in order to show sellers their artworks could fetch a higher price with them. In theory, this sounds great. But this is a classic chicken and egg situation where you need both sellers and buyers to make the marketplace work.

The solution to this conundrum lies in Sotheby’s hunting for buyers further down the value chain (i.e. in products that sell for a few thousand or tens of thousands, rather than 100,000s) and going after buyers of luxury goods and collectables. Previously, these buyers may not have had the interest to purchase high-end art or been intimidated by the art world. By going into an adjacent market with similar characteristics, Sotheby’s has warmed customers with financial means to buy high-end art.

Although I don’t have access to figures to prove this, Sotheby’s has probably managed to increase the total addressable market for high-end art. And it has done so by offering a “buy now” experience as an alternative to its traditional auction model.

Sotheby’s genius insight and subsequent gamble

The art world is still dominated by the traditional auction. But this is not the first time Sotheby’s has ventured into online sales. Twice before the company has partnered with eBay to test the water with online auctions. Neither of these occasions (one was in the early 2000s, the other in 2015) turned out to be raging successes.

However, this time it’s different. Rather than purely going for online auctions, Sotheby’s is finding the “buy now” strategy is proving to be more successful than online auctions. A fixed price offering actually attracts a different buyer to the auction model. Researchers found that fixed prices and “buy now” offerings attract buyers with different needs to those who prefer the auction.

A fixed price offering alleviates anxiety. It is also the reason why eBay expanded into fixed-price selling and saw new growth when it introduced this option after its auction business growth had plateaued. Most of eBay’s transactions today are done on a fixed price model. Other verticals that typically work on a variable price or quote system are seeing growth by introducing a fixed price (e.g. Angi Homeservices). It makes sense for Sotheby’s to follow other companies’ learnings.

In its 2018 annual report, Sotheby’s stated that 60% of its new bidders had come from a digital channel, highlighting how important digital is to the company. Making participation in online auctions and “buy now” transactions more prominent creates an important entry point to the Sotheby’s brand. Those with the wealth and means can move up the value chain (and into high-value art) when they are more comfortable, whilst the rest can build up their collections and perhaps can become important seller clients in years and decades to come.

This strategy also helps reduce overall acquisition costs for Sotheby’s since their client relationships department presumably oversees all transaction data and has the ability to reach out to customers who have the potential to become higher-value customers due to spending habits or particular interests in certain art niches.

Sotheby’s new competitive positioning

With this change in strategy, Sotheby’s is also more actively engaging in a different competitive space. No longer can it just compare itself to Christie’s and other auction house rivals. It is now competing for customers such as eBay (in its luxury segment), RH (in luxury furniture), Net-A-Porter (jewellery, watches, bags etc) as well as niche collector sites (e.g. StockX for sneakers and other collector’s items). Fortunately, Sotheby’s has built up significant brand equity since it was founded nearly 300 years ago. But it will have to make sure that it can continuously attract these newer audiences to its offering.

Whilst personal taste plays a role in some of the items and artworks Sotheby’s sells, there’s also a significant degree of speculation and expected price appreciation that plays a role in many of these purchase decisions. Viewed by that angle, Sotheby’s also competes with stockbroking platforms (e.g. Fidelity, Charles Schwab, Robinhood), private wealth managers and the other investment asset classes (e.g. property investing). Whilst Sotheby’s will likely downplay this aspect, it’s nonetheless worth considering and will likely feed into the company’s positioning strategy.

The start of a growth fly-wheel?

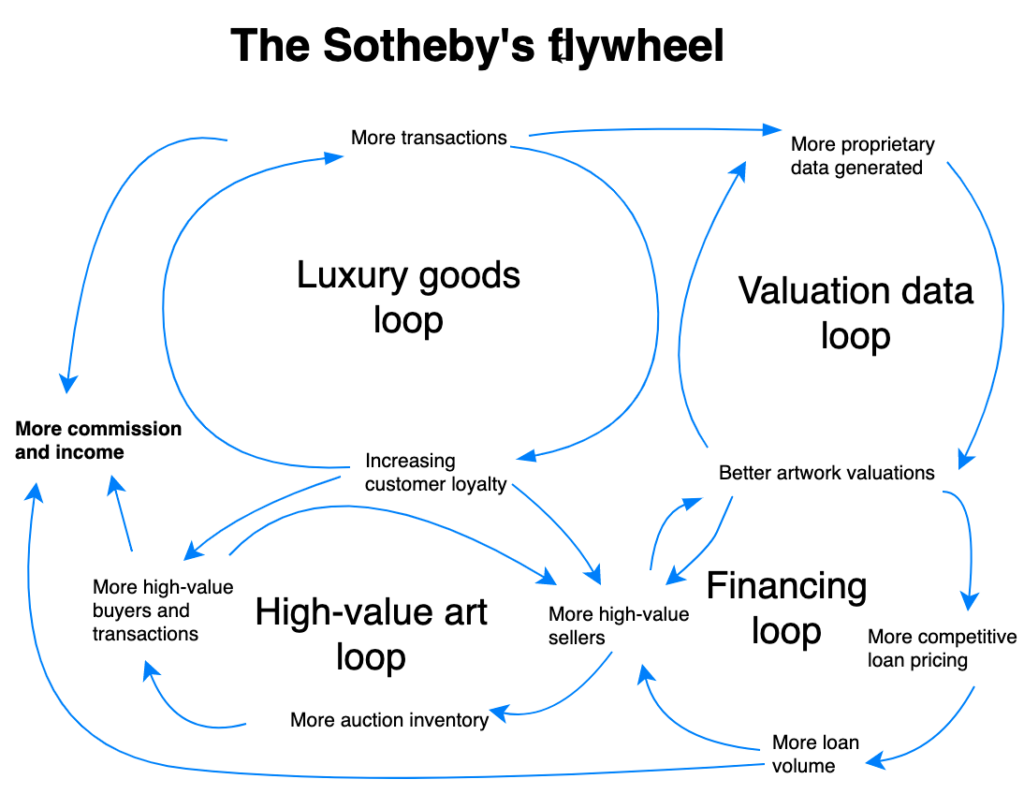

If the diversification to lower-priced products continues to bear fruit, it could gather a positive feedback loop to Sotheby’s business model.

Sotheby’s growth loops

Firstly, by increasing the number of ecommerce purchases buyers make on its site, Sotheby’s would be netting more regular fees. The auction calendar is typically heavily weighted towards the second and fourth quarter of the calendar year, but the ecommerce offering could smooth these peaks and troughs out by enabling transactions all year round.

Secondly, if the company increases the frequency that buyers come to its website to discover and purchase new products, it should be able to keep a lid on customer acquisition costs. In addition, it can also build a solid relationship with buyers, getting them into a habit of opening the Sotheby’s app or online catalog which may also help sway their decision to use Sotheby’s if they need to sell anything from their collection.

Thirdly, the increase in data generated on what artworks and styles are en vogue at any one point in time can help create better valuations in all of Sotheby’s businesses. The art market is notoriously volatile which makes it hard to predict and forecast. By keeping tabs on more frequent lower value transactions, Sotheby’s could gain a data advantage in its higher value sales business and its lending business. In the latter field, due to the higher number of transactions, Sotheby’s could provide more competitive rates as it wouldn’t need as much margin of safety. Naturally, this data can also be used to persuade collectors who are mulling the sale of a certain piece that “now” is the right time to get a good price.

So far Christie’s has not followed in Sotheby’s footsteps and has decided to focus its resources on higher-value segments. Christie’s strategy during the pandemic has been limited to iterating in its auction format, something that Sotheby’s is doing as well.

However, if Sotheby’s strategy succeeds, Christie’s may struggle to catch up as Sotheby’s could build out its lead with its ecommerce and fixed-price offering. As network effects gather pace and Sotheby’s continue to build on its strengths, it will be harder for Christie’s to follow suit. The knock-on effects could mean that Christie’s would only be able to compete by providing sellers with more financial incentives and guarantees to keep up. At the same time, Sotheby’s could use its increasing data advantage and buyer pool to do the job of attracting more sellers to its offering.

It’s still early days and Sotheby’s needs to execute well to make this work. It will take further investment in ecommerce capabilities for Sotheby’s to continue down this path, but the initial momentum and lead the company has taken over its rival is promising.