Spotify’s Net Promoter Score is 51 (NPS is a measure of customer love, the scale ranges from -100 to +100, so 51 is really good). On the surface, they are successful and enjoy a lot of customer love. But Spotify is actually a commoditised business, which leads to low pricing power and low margins.

Unlike Netflix, who can regularly increase prices, Spotify is at the mercy of its suppliers (the music labels) as most of its revenue passes back to them. The big 4 music labels have a 75% combined market share which allows them to dictate terms. Because Spotify pays a very high fixed % of its music streaming revenue to the labels, Spotify, somewhat bizarrely, wants subscribers to use its main product less.

The company has tried to break the labels’ grip on its cost base with its move into podcasting. Podcasting was meant to drive more non-music streaming, which would reduce the payouts to the labels and give Spotify more control over its cost base. But it didn’t work out that way, hence the layoffs.

Spotify’s new bet is audiobooks. Premium subscribers now get access to up to 15hrs of audiobook listening, and Spotify is betting that this will lead to a) more revenue as you can top up your hours if you run out and b) less music listening.

It’s also a win for book publishers who are heavily reliant on Audible (the giant in the audiobook world).

If Spotify is successful, it can build a bigger presence in the audiobook space, potentially building a second revenue stream and driving higher ARPU (Average Revenue Per User). But I am sceptical.

Why am I sceptical?

Two reasons:

– Different usage patterns. Although there’s overlap, music is listened to in different situations compared to audiobooks (e.g. gym, social settings etc). There are different ingrained habits to consider.

– Spotify’s high NPS. Users love the product. Will they move to audiobooks? Perhaps, but music listeners are a huge group who love Spotify’s music streaming product. Most of them are unlikely to start listening to audiobooks.

Spotify’s challenge with differentiation underscores the importance of establishing how different you are from other solutions out there right from the outset. It’s very hard to add differentiation to an established and much-loved product. It’s not that Spotify is a failure. It’s a massive success, but its potential now is limited. Perhaps it will “just” be the world’s largest music streaming service.

Startups nowadays would do well to review their market and take an honest assessment of whether they are different enough to command a premium over competing solutions.

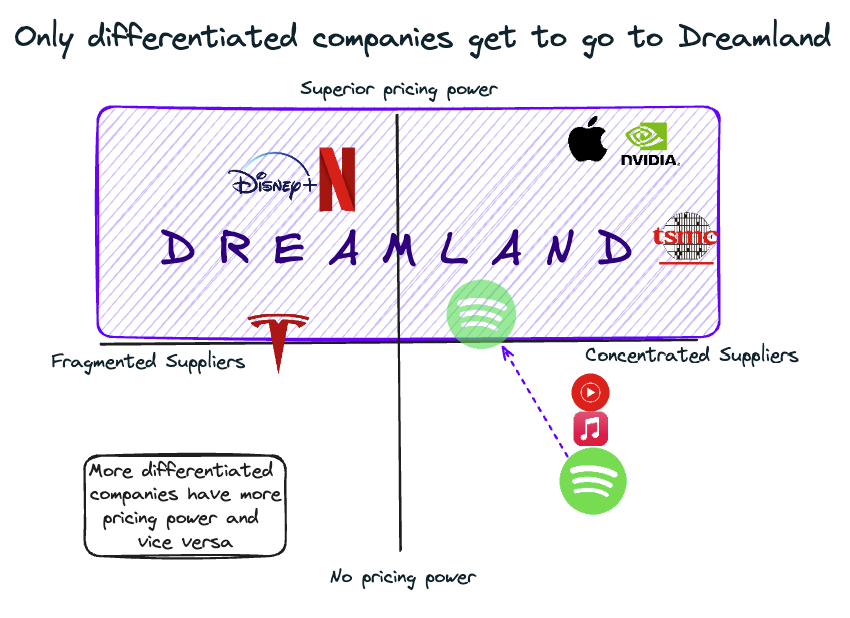

How do other tech companies compare on the pricing power vs supplier fragmentation matrix?

Spotify is trying to move into “Dreamland” by diversifying its supplier base

One of the ways companies can get superior pricing power is by being highly differentiated. In the diagram below, you could do with labelling “Dreamland” as “Differentiation Land”.

For example, Disney+ and Netflix work with thousands of different TV and Movie production companies who produce their content. In the UK alone there are over 1300 of these and both companies operate on a global scale. This gives them the upper hand when it comes to negotiating with their suppliers and importantly they often negotiate exclusive rights which means their newer content is often only available on one streaming service. If you want to watch Stranger Things, you have to go to Netflix whilst Moana is only available on Disney+. That’s their differentiation which means they are able to increase prices fairly consistently.

Nvidia and TSMC have technological differentiation. For Nvidia, you can’t find their chips anywhere else and combined with Cuda their proprietary coding language you just need to look at the most recent stock price appreciation to see that they have pricing power. TSMC has the fabs that develop the most advanced chips on the planet (including Nvidia’s) which allows them to increase prices.

Apple’s hardware and software combo as well as their ecosystem lock-in make it very hard to move away from once you’re in.

Finally, Tesla is on the cusp of being in dreamland. Their recent price decreases were mostly macro-related (electric cars are very expensive) but their proprietary in-car software is miles better than what most of the competition can muster. Although it remains to be seen whether they can actually properly enter dreamland.

Spotify, YouTube Music and Apple Music are largely commoditised. The music is virtually the same wherever you go. The experience is a little bit different across providers which allows for stickyness. Apple and YouTube have bundles with other products in their ecosystem which helps them offset some of the commodity aspects, but it’s not enough to be able to push through price increases.

Spotify’s audiobook move is geared at helping them to enter or at least approach Dreamland. But we shall see if they’re able to.

If you enjoyed this read, hit subscribe below to get an essay like this. Every so often.