When Jim Barksdale was preparing for his company to go public in 1995, he left a room full of bankers baffled as he finished his speech:

“Gentlemen, there’s only two ways I know of to make money: bundling and unbundling.”

And with that said, he left the room.

Jim was the CEO of Netscape, one of the biggest and most successful tech companies of its time. Later that year the company went public, but the quote still resonates today.

Bundling and Unbundling are business product strategies employed to react to shifts in their markets. As customer needs evolve, startups and companies win market share by being nimble and adjusting to shifting customer needs.

If done successfully, companies benefit from a differentiated product offering to their competitors. From startups to massive multi-nationals such as Netflix and Apple, bundling and unbundling has unlocked billions of dollars in value. Using plenty of examples, this essay serves as an introduction to understanding the nuances of how and when these strategies could be applied.

What is bundling? What is unbundling?

At its simplest, bundling is when companies package different product offerings together. Think of Cable TV bundling sports, movies, box sets and reality TV in a single offering for the viewer’s convenience.

Unbundling then is the exact opposite, where a company focuses on one product that was only available as part of a bundle before this. Netflix unbundled the Cable TV bundle by offering movies and box sets in a simple standalone package.

So why do companies bother? Why could bundling and unbundling lead to long-lasting business growth?

Why bother (un)bundling?

It’s all about gaining customers and building market share. Companies go through the painful process of bundling and unbundling because they believe their new offering will lead to more customers. They differentiate their products so that when their ideal customers come to make a buying decision, the new product should best meet their needs.

In mature markets with established competitors, products or services may seem very similar to each other. This is not accidental. These competitors have all created products that target the needs of the largest group of customers. Therefore the products are mostly undifferentiated, the same or relatively similar. In theory, capturing the majority of customers should also deliver the majority of the profits. However, many smaller companies can still do very well by focusing on customer needs for the non-majority.

In many industries you can still build a great company if you capture just a couple of percent of the existing market. Going after non-majority customers is the sweet spot where bundling and unbundling can unlock value. All you need is one company brave enough to decouple itself from the majority and focus on a lucrative minority segment.

A note about competition and minority customers

Competition is mostly defined as other companies actively going after your customers. But you might also have other forms of competition. Minority customers might not even be served at all by any of your direct competitors. Some products (especially innovative ones) compete against legacy solutions that ‘get the job done’. For example, many B2B or analytics startups compete with spreadsheets. Why? Spreadsheets are so versatile, that many tasks do not need any other tool. An analytics startup that has identified spreadsheets as a competitor in their chosen target customer base then may have to overcome the spreadsheet to target that specific segment of customers.

Alternatively, companies could be competing against ‘non-consumption’ as well. As an urban resident, you might evaluate the purchase of a car against other modes of transport (e.g. taxi, bicycle, walking, public transport, etc). Car manufacturers understand that they are not just competing against other manufacturers but other modes of transport.

Both in bundling or unbundling, your product or service therefore also benefits from exploring ‘legacy solutions’ and ‘non-consumption’. They may not be the right customer to go after, but there may be some hidden gem customer groups that your new product may serve particularly well.

Bundling

As we’ve explored already, when a company bundles, they combine different products or services to make their offering more attractive to customers. It’s a convenience play. We’ve looked at Cable TV already, but newspapers do a similar thing. They bundle news covering politics, business, sports, so that readers can read everything in one paper and don’t need to look elsewhere to get their news fix.

Bundling works well in the media, but it also works just as well in consumer electronics:

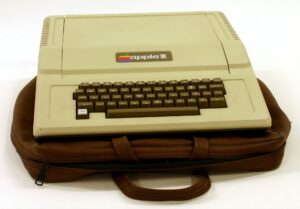

How Apple bundled its products to be simpler

Often companies in complex markets will bundle products together to simplify the proposition.

Apple launched the Apple II computer in 1977 when personal computers were a novelty. In total it sold over six million units which was incredible given the small PC market at the time. One of the main selling points to consumers was that the hardware and software were bundled into one package creating a great customer experience.

Apple’s strategy over the last 40 years or so has been to bundle products and make them work seamlessly with each other. For many customers, technology presents a headache. But Apple’s products remove some of that risk and are perceived to just work.

Apple II computer by Museums Victoria on Unsplash

What’s great about bundling is if it’s done right, the business doesn’t just win existing market share from competitors. It also gains non-consumers as customers who before may have thought it was ‘not for them’. This is why the Apple II was so successful. The product simplified the decision making experience through bundling.

Fast forward a few decades and bundling applies to modern day eCommerce websites too…

How Patch bundled plants to target new customers

Patch is a Direct to Consumer (DTC) online plant shop in the UK. When they first started in 2015, millennials were badly served by garden centres and existing online plant websites. Prospective customers new to plants faced confusing latin plant names and most garden centres were in out-of-the-way suburban locations.

So urban-dwelling millennials didn’t buy plants and thus were largely non-consumers. But Patch recognised the opportunity. Aligned with a growing houseplant trend, it bundled an accessible ‘plant parenting’ course to educate customers on how to look after their plants together with its online plant shop. The company also added a ‘Plant Doctor’ aftercare service that advised customers on how to treat unwell plants. When you’re new to having plants in your home, there’s a good chance you might kill your plants. The Patch bundle removes some of that risk.

Plant parenting courses and Plant Doctors helped win new customers for Patch’s eCommerce business and helped differentiate the company to capture a fast-growing segment of the market.

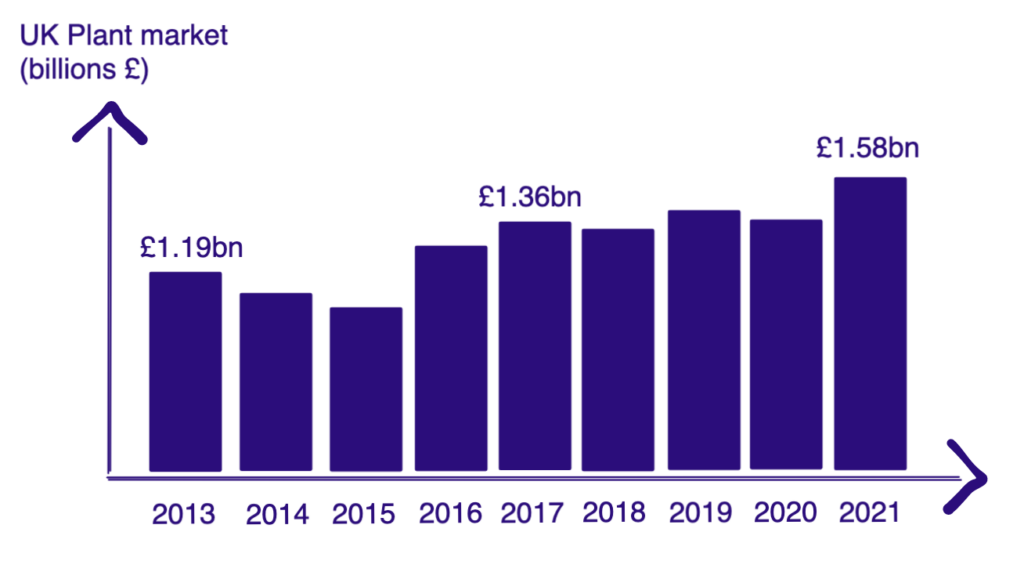

A changing plant market

Plant growth. Source: UK Government

The houseplant trend caused a previously stagnating UK decorative plants market to grow from £1.19 billion in 2013 to nearly £1.6 billion in 2021. Lots of inexperienced younger customers entered the market. And Patch’s bundled offering was perfect for their needs, unlocking the company’s rapid growth.

How Opendoor bundled real estate transactions

Another example of bundling is Opendoor’s US home buying service. Opendoor offers a convenient solution to home sellers that bundles the real estate agent and house buyer into one service. This reduces the time spent on a typical real estate transaction from months down to weeks. But it also reduces the risk of the sellers’ properties languishing on the market. It’s not an add-on to the core business (as we’ve seen in the Patch example). Instead, it’s a reinvention of the entire real estate broker business model. Opendoor themselves buy the house and provide the cash for the transaction, then sell it on the open market pocketing a transaction fee in the process.

Opendoor is now a rapidly growing $4 billion market cap business. Their bundling strategy didn’t change the total size of the market. But instead it differentiated Opendoor enough to take market share from competitors.

Why Amazon created its customer bundle: Amazon Prime

A few of the Amazon Prime membership benefits

Bundling many unrelated services together is the strategy that Amazon is pursuing with Amazon Prime. Free and fast shipping, video-on-demand and music streaming are a few unrelated products bundled under Prime. Except for expedited shipping, these could all be standalone businesses.

But Amazon is bundling the offerings together to offer value and encourage customers to keep shopping with Amazon. It’s an advertising and engagement strategy where the Amazon brand is always front and centre. How so? The Amazon product search bar is always a click away when you’re watching a movie or listening to music. It’s likely one of the reasons why half of US internet users start their product research on the Amazon website. After all, the search bar for the ‘everything store’ is right in front of them already.

Today, Amazon has over 200 million global Prime subscribers and is one of the most valuable companies in the world.

Types of Bundling Strategies

We’ve touched on how bundling has helped companies differentiate from the competition. But it’s not just about targeting and attracting new customers. It’s also bundling in a way that plays to target customers’ needs or grabs their attention:

Bundling to remove perceived risk

Patch, Opendoor and Apple all belong in this category. These companies have bundled products or services together to strengthen their value propositions. Their bundles remove perceived risks thereby lowering barriers to purchase.

Patch helped expand the market with the influx of younger demographics, whereas Opendoor captured existing customers from competitors.

Bundling for customer engagement

Bundling can lead to more customer engagement and more regular purchases. Amazon Prime is a good example but it is not the only company to do this.

Intuit (who own TurboTax, a tax prep company) bought Credit Karma (a free credit monitoring and building service). Why? Because Credit Karma is a tool that gets monthly visits from many of its users wanting to improve their credit scores. Credit Karma’s users are also the perfect customer for TurboTax, allowing the latter to engage and acquire CK’s users as customers. If you want more context, here’s a great write-up on Stratechery on the Credit Karma and Intuit deal.

Bundling to launch new products

Although this is not a differentiation strategy, it’s also worth mentioning that many companies use bundling as a launch strategy for new products. Microsoft launched Teams as a free product within their existing Office 365 subscriptions gaining millions of users on Day 1. Teams has grown a lot since then and is now a close competitor to Zoom in the video meeting space.

Apple is also not shy in pre-installing Apple Music, its music streaming service, on Macs and iPhones. Or in pushing iCloud storage services to Apple users. However, it goes without saying that you need a big customer base first before you can successfully launch new products like this.

Unbundling

Bundling and unbundling follow the same strategy of meeting unmet or underserved needs of some customer groups. Unbundling most often happens in relatively mature markets that are ripe for a change.

Mature markets usually have competitors who have conformed towards a similar product offering serving the majority. Because in theory, the majority of profits lie there.

Companies who unbundle usually are not market leaders. They’re often startups who want to target smaller groups of customers with simpler needs and are overserved with market leaders’ products.

How eBay unbundled classified ads, then ‘got’ unbundled themselves

eBay was born to unbundle. The company’s auction model was perfect for sellers who previously advertised in newspaper unclassified sections. Except, with eBay they could service customers from all over the country. With eBay’s auction model, the company grew to be one of the Web 1.0 giants.

But more recently eBay has suffered from being unbundled itself: Depop and Poshmark have unbundled second hand fashion sales from eBay. StockX has unbundled sneakers. Etsy has unbundled various crafts.

In each of these cases, having customised eCommerce offerings created a better customer experience than a one-size-fits-all model that eBay offered. For example, StockX verifies that the sneakers are genuine before money changes hands, protecting the buyer from counterfeit products and also making it hassle-free for the seller. Unless eBay starts to customise its offering to these sellers and buyers, it will likely lose these lucrative product categories for good.

How food delivery apps unbundled the takeaway

Uber Eats, Deliveroo and other food delivery apps are the unbundling of the restaurant takeaway. The apps are creating a more convenient way of having takeaway foods delivered home. But unlike other unbundling examples, this one is a net positive for the entire industry. It is beneficial to restaurants (more revenue) and customers (more takeaway options delivered home). Their competition comes from supermarket ready-meals and home-cooked meals.

My friend Liam Nolan pointed out that whilst Deliveroo was certainly unbundling the takeaway from individual restaurants, the company also bundled access to multiple restaurants into one app/website. It highlights that one can look at bundling and unbundling on different spectrums. Sometimes the best startups pick and choose the (un)bundles that deliver the best experience for their target customers.

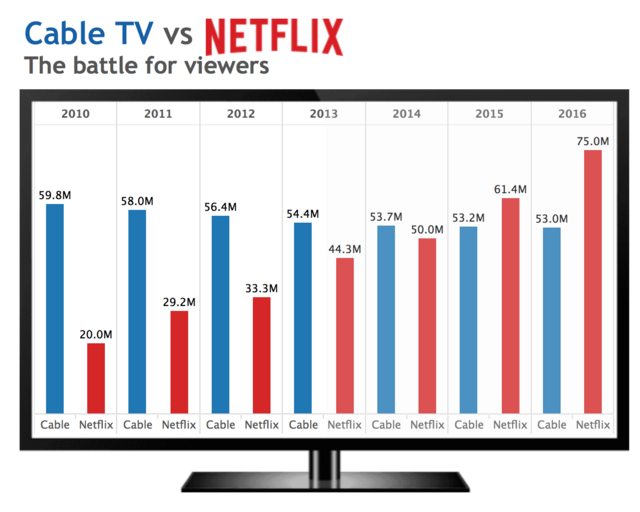

How Netflix unbundled Cable TV

Unbundling the US Cable TV market has been one of Netflix’s great achievements. Previously, expensive and massive content bundles were attached to long term and inflexible contract terms. Along came Netflix offering an inexpensive monthly contract with lots of content available on-demand.

Netflix broke up the integrated offering, focussed only on films and series (e.g. no sports or news) and also unbundled set viewing times for programmes by offering the on-demand menu. When you look at graphs of Netflix’s subscriber growth, it’s obvious that they were attracting not just Cable TV cord-cutters but also many more households who’d never signed up for Cable TV (see below).

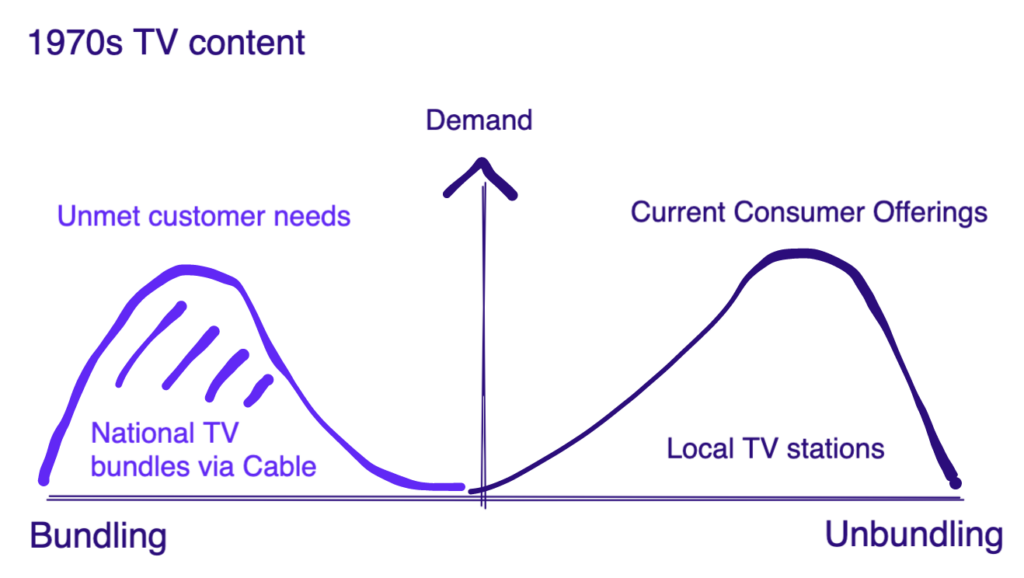

TV content: Bundling, Unbundling, and back again?

Over the last half a century, the TV content market has experienced a period of bundling and unbundling. And it may even get bundled together again in the coming years.

The opportunity was firmly in bundling territory in the US

In the US, terrestrial TV stations previously only aired content locally and many viewers in inaccessible regions couldn’t receive their local stations. Telecoms companies were formed to port this content straight into households via cable. They then realised they could also start serving non-local content to their customers and charge more for this service. It was a great deal for cable customers too, because they could get access to much more content than a normal TV aerial could receive. This was the first wave of bundling that started in the 1960s/1970s and was driven by Cable TV companies (e.g. Comcast) investing billions into cable infrastructure.

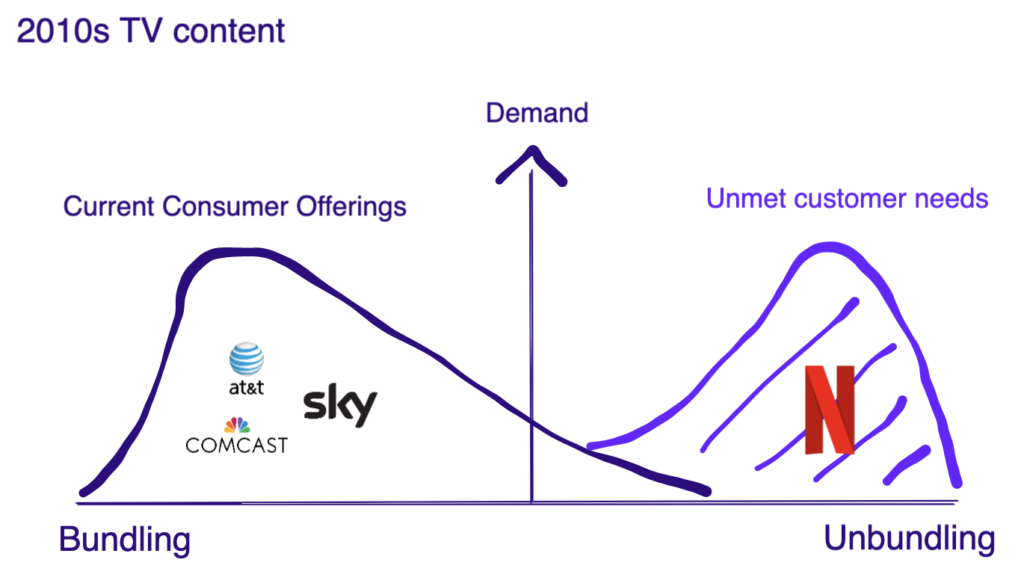

2010s – Moving back towards unbundling

However, a few decades later Netflix launched its streaming proposition. The opportunity arose because broadband speeds were now fast enough to make content available on-demand. And because Netflix didn’t have to create the infrastructure to pipe this content to its customers, it could charge a much lower fee than Cable companies did for their TV bundles. Netflix unbundled Cable TV. But as we’ve seen earlier, it initially increased the market for paid-for content by attracting many new customers in the space who didn’t have or care to pay for Cable TV. But they were happy to pay for Netflix’s unbundled product.

The tables reversed and the opportunity was in Camp Unbundling in the 2010s

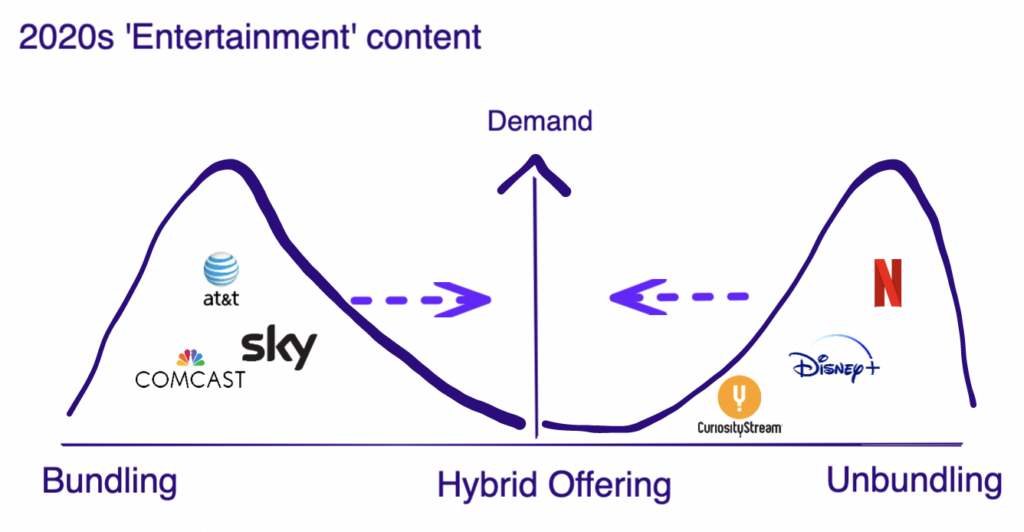

2020s – Convergence towards the centre?

More recently, Netflix has suffered a dip in subscriber numbers after peaking at just north of more than 200 million globally. Many commentators have speculated that we’ve now seen peak demand for content subscriptions. With the arrival of many new on-demand streaming services (e.g. Disney+, Peacock etc), the balance could shift again towards content bundles. Streaming services have partnered with traditional cable TV companies to bundle in their content services in order to reach more consumers and reduce their acquisition costs.

Quo vadis in 2020s?

Cable TV companies have been eager to partner with these services. They argue that this move could increase their own retention rates amid a flurry of ‘cord-cutting’ that occurred in the 2010s as some customers opted for Netflix et al instead of Cable TV. Bundling these services together could be a win-win for all parties. But there’s also a different kind of bundle that Netflix is exploring…

The ‘TV and Games’ bundle

Over the last year, Netflix has been exploring how they could differentiate themselves by offering a games bundle. Primarily aimed at casual gamers, the company seems to be taking a view that expanding into a different vertical could increase retention rates and possibly allow for a new revenue stream on top of existing subscriptions.

Netflix has argued that it sees video games more as competition than other streaming subscription services. Since both games and video streaming content are consumed during leisure hours.

Interestingly, Netflix’s offering could start to resemble more like Amazon’s Prime bundle with many different content types under one roof (minus the shipping part).

Time will tell whether this bundle will prove successful for Netflix. But if it does, you could definitely see Disney and other companies with valuable intellectual property explore this option too.